The Disappearing Ski Town of Tucson, Arizona

How a Changing Climate Is Erasing the Southernmost Ski Area in North America

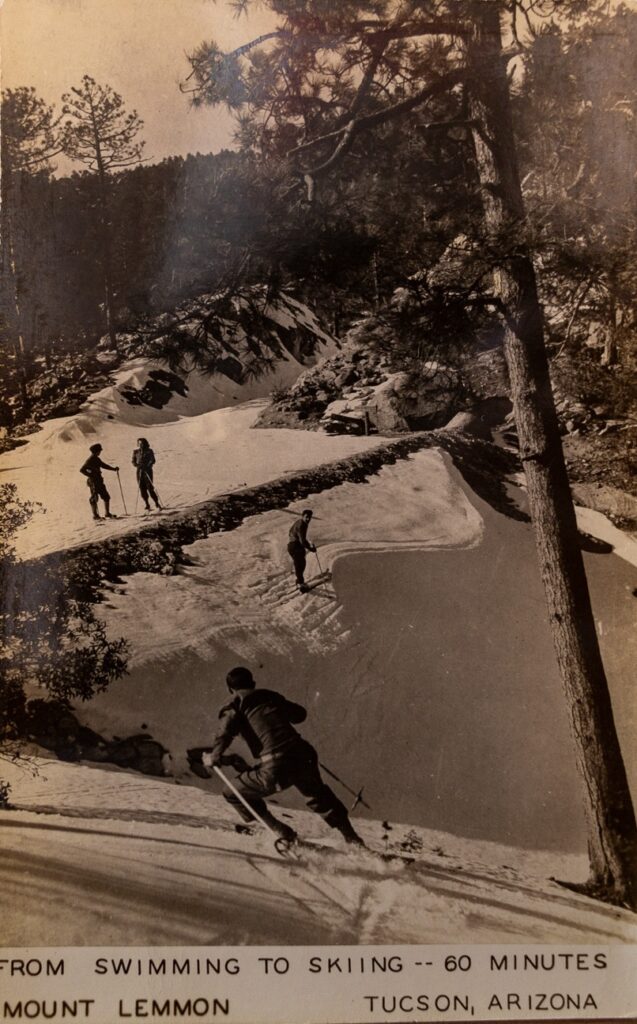

“Skiing began early in November this year,” reported The New York Times in 1961, describing a surprising winter scene—skiers carving turns on snowy slopes just 40 miles from downtown Tucson, Arizona. “By Dec. 1, there was a foot and one-half of hard-packed snow on the north and east slopes,” the article continued, portraying a season that “generally begins just after Christmas and runs well into March.” Beyond documenting snowfall, this snapshot from the past reflects something deeper: a time when the idea of skiing in the desert felt entirely natural, fitting seamlessly into what scholars of science and technology call our “sociotechnical imaginaries”—the shared visions of what a place can and should be.

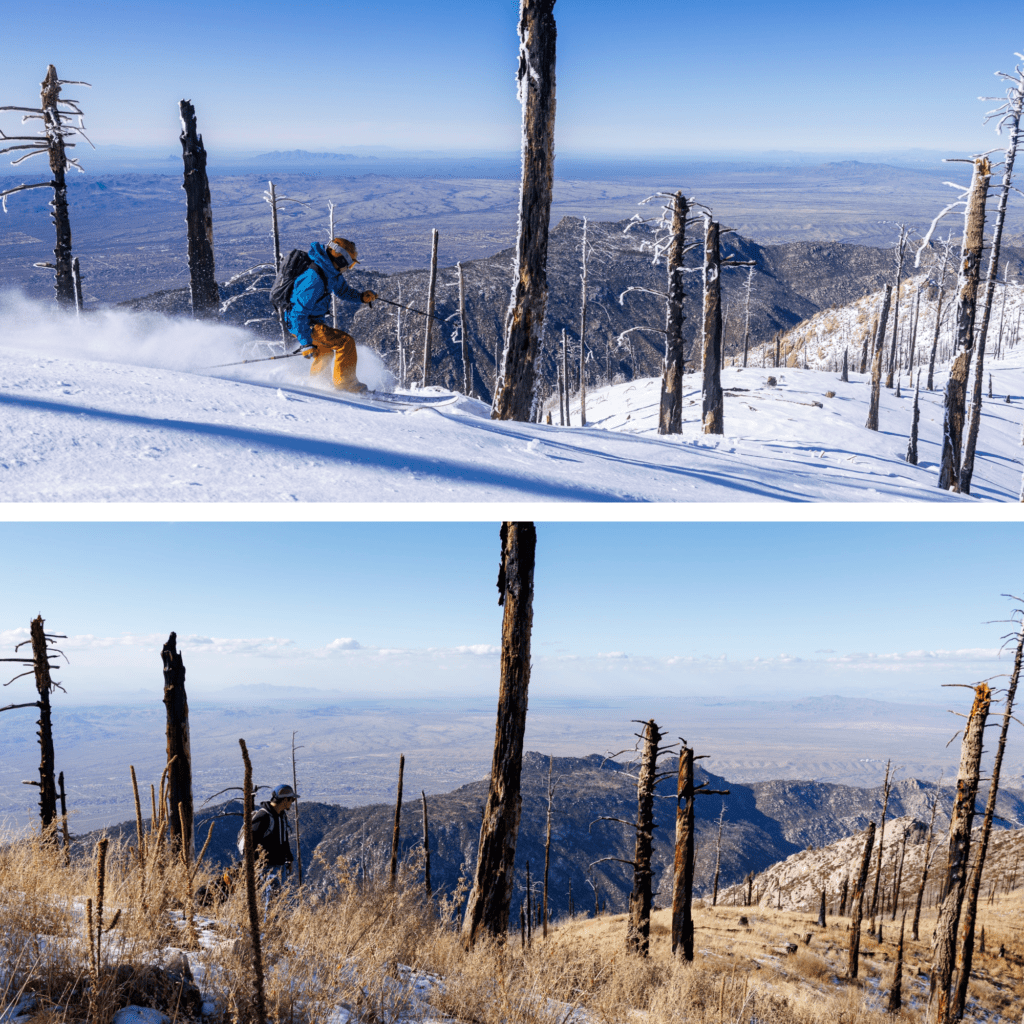

A bead of sweat slowly trickled down my temple in January 2023 as I stood among the fresh powder and the piercing bluebird sun with my camera, waiting for friends to drop down Mount Lemmon’s slopes. The scene before me seemed to challenge our contemporary understanding of what belongs in the Sonoran Desert—snow-covered peaks rising above cacti-studded valleys, the mountain ranges of northern Mexico shimmering in the distance. A powerful storm system had just deposited over two feet of snow, though accessing it meant navigating around the Sheriff’s notorious tendency to close the entirety of the highway up the mountain at the slightest hint of precipitation—a practice reflecting how our institutions struggle to reconcile desert infrastructure with alpine conditions. Two years later, standing in the same spot, I framed my lens on the same slope—this time, only brittle golden grass and the blackened husks of trees remained, the snow long forgotten. The contrast is staggering, a visual timeline of a vanishing winter. These paired images capture more than just environmental change; they document the dissolution of what historian of science Deborah Coen, in Climate in Motion, calls ‘regional climatic cultures’—historically situated, localized understandings of climate shaped by social, political, and scientific practices that once defined what constituted normal weather.

This transformation becomes even more striking when viewed through the lens of how we imagine and measure environmental change. Today, we count ourselves lucky if we can ski from mid-January to late February—a season barely half as long as what skiers enjoyed sixty years ago. A recent 2024 New York Times article, “36 Hours in Tucson,” makes no mention of skiing at all—a stark contrast to the 1961 characterization of the region and its allure. Its absence reflects a deeper shift in how we perceive and understand climate change. As scholar Sheila Jasanoff describes, our collective knowledge about the environment isn’t just shaped by science but also by culture and institutions—what we choose to acknowledge, record, and act upon as evidence of change. The dramatic shortening of the season isn’t just a matter of lost recreation; it represents a fundamental shift in how we collectively perceive what is possible in this landscape.

As North America’s southernmost ski area, Mount Lemmon serves as a canary in the coal mine for the challenges ski areas face in a warming world. Without artificial snowmaking capabilities—a practical impossibility given the region’s water scarcity and increasingly marginal temperatures—the resort relies entirely on natural snowfall. While it has only failed to open once since its founding during the 2010s and barely operated during the 2018-2019 season, these closures signal more than just a climatic trend. They illustrate what Bruno Latour, in We Have Never Been Modern, describes as the ‘hybridization’ of nature and society—the breakdown of artificial boundaries between environmental systems and human institutions. As snowfall patterns shift, governance structures, infrastructure planning, and even recreational expectations are forced to adapt, revealing the extent to which climate is not just a backdrop to human activity but an active participant in shaping social and institutional change. Yet perhaps most striking is the lack of long-term scientific records; the Santa Catalina Mountains, where Mount Lemmon sits, have no SNOTEL stations and no systematic snowpack measurements. This gap in monitoring highlights what Bruno Latour describes in Politics of Nature as the selective recognition of environmental change—some landscapes and climate shifts are studied and discussed, while others are overlooked and effectively erased from official records. As skiing disappears from both our collective memory and regional identity, the story of this shrinking snow zone is left to community recollections and scattered photographs—fragile traces of a winter that is quietly slipping away.

From Lowell Thomas’s Desert Ski Dream to the Dystopian Sonoran Avalanche Center

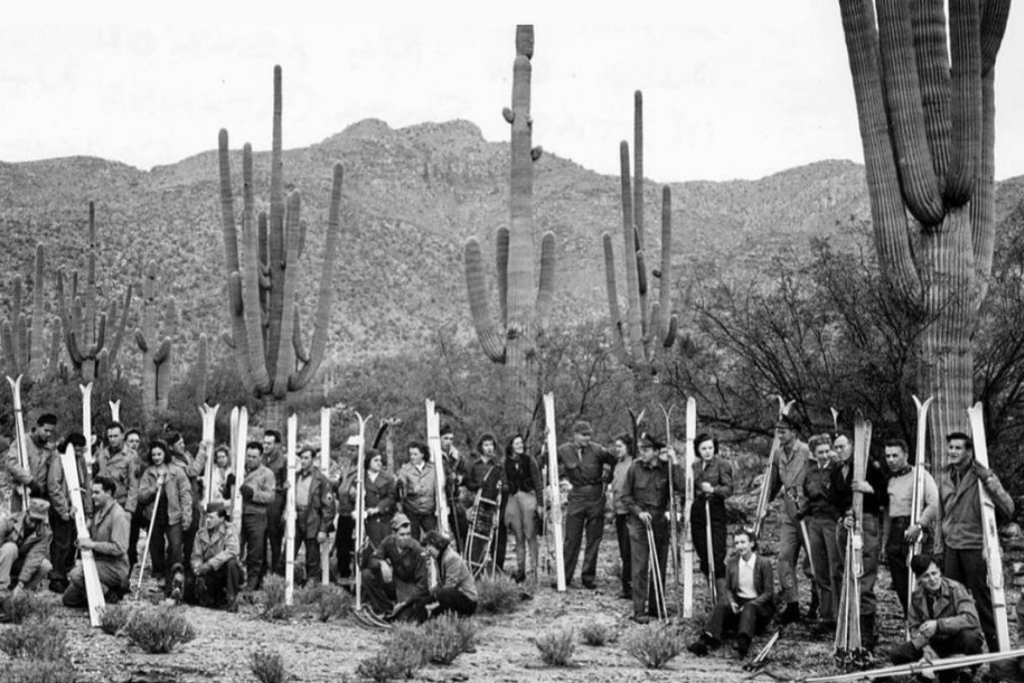

Mount Lemmon’s ski history is the result of an unlikely collision between desert dwellers and alpine enthusiasts, brought together by one of American skiing’s most influential figures. Lowell Thomas, the famed broadcaster and journalist who helped popularize skiing across the United States, co-founded the Sahuaro Ski Club alongside servicemen from Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in the final days of World War II. Thomas had already played a key role in developing Sun Valley, Idaho, and through his widely broadcast radio shows, helped turn skiing into a mainstream American pastime. Yet even for him—someone who had seen the sport take root in improbable places—the idea of carving turns above the Sonoran Desert must have seemed surreal.

The club’s founding members included Thomas’s son, Lowell Jr. (who would later become the governor of Alaska), and Art Devlin, an Olympic ski jumper and future broadcaster. This mix of well-connected ski advocates and local military personnel created a community that balanced serious sport with a sense of novelty. Cartoonist Paul Webb captured this odd charm in the club’s now-iconic patch: a skier wrapped around a saguaro cactus—a fitting emblem of the peculiar joy of desert skiing. Thomas, always a showman, turned the club into more than just a curiosity, sending honorary memberships to celebrities worldwide and helping establish Mount Lemmon as a legitimate, if unconventional, part of American skiing’s postwar expansion.

But today, Mount Lemmon’s story is anything but lighthearted. As the southernmost ski area in North America, it has become a warning sign for the future of winter sports in a warming climate. Unlike higher-elevation resorts that can rely on artificial snowmaking, Mount Lemmon has no such lifeline. Making snow requires sustained temperatures below 28°F and a steady water supply—both increasingly rare in the Southwest. The resort has operated most years since its founding, but in bad winters, it barely opens at all.

This rich history of desert skiing, coupled with the mounting challenges of climate change, inspired an unlikely project: the Sonoran Avalanche Center. When I founded it in 2022 with two other friends, the idea of avalanche forecasting in the Sonoran Desert raised more than a few eyebrows—much like the original Sahuaro Ski Club did decades earlier. But the center serves a deeper purpose than just tracking snow conditions. It’s an exercise in documenting the improbable: the confluence of desert and alpine environments in an era of rapid change and to craft narratives and conversation around it. While we may issue only a handful of forecasts each season (and sometimes none at all), each one represents a rare moment when the desert transforms into something altogether different. Like Thomas and his ski club before us, we’re creating a record of these fleeting intersections between desert and winter, knowing they may become even rarer in the years ahead.

The Ecological Web of Sky Island Snow

The disappearance of snow in the Sonoran Desert has consequences far beyond skiing. Mount Lemmon is part of Arizona’s Sky Islands—a network of isolated mountain ranges that rise abruptly from the desert floor, much like islands emerging from the ocean. These peaks, ranging from 3,000 to over 10,000 feet in elevation, create a patchwork of distinct ecological zones, each supporting unique plant and animal life. For millions of migrating birds and other species traveling ancient routes between the American Southwest and Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains, these high-altitude oases serve as critical stopover points. It’s one reason Tucson is one of North America’s premier birding destinations.

While the snow that falls on the Sky Islands isn’t a primary water source for Arizona’s cities—most of which rely on the Colorado River and deep aquifers—it plays an essential role in the region’s water cycle. Unlike the dramatic summer monsoons that drench the desert in short, intense bursts, winter snow provides slow, steady moisture as it melts. This gradual release of water seeps into the ground, replenishing local aquifers and sustaining the mountain springs and seasonal streams that many plants and animals depend on. Historically, this winter snowpack has acted as the Sonoran Desert’s “second wet season,” delivering moisture through spring and early summer—precisely when desert ecosystems need it most.

The way snow behaves in these mountains is particularly crucial for maintaining ecological stability. The gradual melting process creates what ecologists call a “pulse-reserve” system—where water is stored as snow in the colder months and released gradually, sustaining different plant and animal communities at varying elevations. This pattern is especially vital for Mount Lemmon’s old-growth conifer forests. Trees like Douglas fir and Ponderosa pine rely on consistent spring moisture from snowmelt to survive. Snow cover also acts as a natural insulator, shielding soil microorganisms and plant roots from the extreme temperature swings common in desert environments.

When snowpack declines, the ripple effects spread across the entire ecosystem. Research has shown that in years with low snowfall, tree mortality increases, and understory vegetation—smaller plants that grow beneath the forest canopy—suffers significant losses. This impact is particularly severe in the transition zones between 7,000 and 8,500 feet, where desert and alpine ecosystems overlap. These bands, known as “ecotones,” are highly sensitive to climate change. Even slight changes in temperature and moisture availability can disrupt entire food webs—from soil fungi to apex predators. One species particularly at risk is the Mexican spotted owl, which relies on these mixed-conifer forests for nesting and hunting. As snow disappears, the cascading effects could permanently alter these high-altitude habitats, reducing their ability to support the diverse life that has evolved to depend on them.

Measuring What We’ve Overlooked

Despite being home to a ski area since the 1950s, Mount Lemmon lacks the kind of long-term snow data that typically accompanies such operations. There are no SNOTEL stations, and no systematic snowpack records—an absence that is more than just an oversight. It reflects a deeper assumption about where snow is expected to exist in the American landscape. Unlike the Rockies or the Sierra Nevada, where snowfall is critical for regional water supplies and agriculture, the Sonoran Desert has never been considered a place where snow “matters” enough to measure. The idea of formally monitoring snowfall in this environment may have seemed unnecessary, even illogical, to the agencies responsible for tracking hydrology and climate trends.

Historically, snowpack monitoring in the U.S. has been driven by concerns over water availability, particularly in regions where melting snow provides a primary water source for cities and agriculture. Organizations like the USGS and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) prioritized SNOTEL installations in the West’s high-elevation watersheds, where snowmelt is a critical input to reservoirs and irrigation systems. Because Mount Lemmon’s snowpack is not a major contributor to Arizona’s water supply—especially compared to the Colorado River—there was little incentive to establish formal tracking infrastructure. Instead, state and federal agencies focused on monitoring snowfall in the White Mountains, the Mogollon Rim, and Flagstaff, where water runoff plays a more direct role in hydrological planning.

Even the University of Arizona, a leading institution in climate science and hydrology, did not prioritize snow monitoring on Mount Lemmon. While the university operates numerous climate and ecological research projects in the Sky Islands, its focus has largely been on temperature trends, monsoon patterns, and biodiversity shifts—areas that align with broader scientific and policy concerns about desert climate change. The university’s snow-related research has historically centered on Flagstaff’s high-altitude watersheds and the Rocky Mountains, where water managers depend on snowpack forecasts to plan for drought conditions.

This lack of formal monitoring presents a significant challenge: without long-term snow data, how do we quantify just how much Mount Lemmon’s winters have changed? At the same time, this gap forces us to rethink how we document environmental change and highlights the importance of blending different kinds of knowledge. Scientific measurements are invaluable, but they are not the only way we understand the world. As Sheila Jasanoff describes in her work on science and society, what we choose to measure—and where we choose to measure it—shapes not only our understanding of the environment but also our response to it. Similarly, Paul Slovic’s research on risk perception shows that people grasp environmental threats not through abstract statistics, but through lived experiences—through the changes they can see and feel in the places they know.

On Mount Lemmon, where no official snow data exists, these insights become especially relevant. A longtime skier’s memory—that winter conditions once lasted reliably from December through March—is not just nostalgia; it’s a data point. When paired with historical evidence—like a 1961 New York Times article that described skiers carving turns in early November—these personal accounts help reconstruct a climate history that institutional science has overlooked. By combining sources like old photographs, newspaper archives, ski area records, and community recollections, we can paint a fuller picture of how winters here have changed. These qualitative records, alongside broader regional climate data, do more than track temperature shifts; they reveal how environmental change impacts both ecosystems and communities—especially those in places that exist at the fringes of our environmental awareness.

This challenge—how to document change in places that fall outside of traditional monitoring networks—is one that historian Naomi Oreskes has explored. Much of climate science focuses on well-studied landscapes that fit our preconceptions of where snow, forests, or deserts “should” exist. But in doing so, it often overlooks the transitional zones—the in-between spaces—where small changes can trigger profound shifts. Large ski resorts in Colorado or Utah have decades of detailed snowpack records, but smaller, marginal areas like Mount Lemmon rarely receive the same attention. And yet, these so-called marginal snow zones may provide some of the most valuable insights into climate change’s effects.

Mount Lemmon’s transformation highlights why these overlooked places matter. Climate models consistently show that winter temperatures in the American Southwest will continue to rise. But to understand what that means at a local level, we need to pay attention to places we once thought were too insignificant to study. Here, where the ski area operates between 8,200 and 9,157 feet, even a slight increase in temperature can push the rain-snow line above critical elevations, altering not only recreation but the mountain’s entire ecological system. The effects extend far beyond skiing: shifts in snowmelt patterns influence wildlife migration, impact regional water supplies, and increase fire risk. As winters become shorter and drier, the risk of more frequent and intense wildfires grows, accelerating the transformation of these high-altitude ecosystems.

By turning our focus to places like Mount Lemmon—places that exist at the edge of where winter has traditionally been seen as reliable—we gain a clearer understanding of how climate change unfolds in real-time. These marginal zones serve as early warning systems, offering insights into how warming temperatures will reshape landscapes, not just here but in mountain regions across the world. Recognizing their importance forces us to reconsider where winter matters and how we choose to document it before it disappears altogether.

What Photographs Remember

I stood atop Mount Lemmon’s ski runs in January 2023, sweat trickling down my temple as the desert sun glared off deep powder. Just days earlier, an unusual winter storm had dropped over two feet of snow—a fleeting spectacle for the southernmost ski area in North America. The air was still, the snow pristine, and for a moment, it felt like a glimpse into the past—when skiing in the Sonoran Desert was not an oddity, but an expectation. Yet even as I framed my shots, I knew this winter was an exception, not the norm. Two years later, in January 2025, I returned to the same spot. The transformation was stark. Where once there had been powder, there was now only bare earth and skeletal, blackened trees—charred remains whispering of the 2020 Bighorn Fire’s destruction. This was not a gradual fading of winter, but a rupture—an abrupt shift that forced a reckoning with how quickly landscapes can become unrecognizable.

Photography, at its core, is an act of witnessing. The images captured from Mount Lemmon over the decades do more than document change; they confront us with the stark reality of loss. Climate models may predict trends, but photographs place us in the moment—forcing us to see, feel, and reconcile the vanishing winter in real-time. These paired images are not just aesthetic contrasts; they serve as both evidence and memory, bridging the gap between scientific observation and cultural meaning. Environmental philosopher Lawrence Buell describes this as environmental memory—a record that fuses the physical remnants of a changing world with the human histories embedded within it.

Each photograph becomes a frozen moment in time, a data point in a place where traditional measurements are absent. Viewed side by side, these images don’t just reveal differences—we feel them. In 2023, the slopes were blanketed in a pristine layer of snow, the white expanse reflecting the brilliant blue of the sky. Just two years later, that same frame is stripped bare, the earth brittle and dry. The contrast is more than visual; it is diagnostic, an indicator of a shifting climate where what was once an anomaly—a snowless winter—may soon become the norm.

The power of visual documentation lies in its ability to bridge the gap between data and experience, particularly in places at the margins of our environmental imagination. Climate models can map trends, but photographs capture the reality of change in a way that people connect with—by making it visible, immediate, and undeniable. Research on risk perception, such as the work of Paul Slovic, suggests that people don’t internalize climate change through abstract statistics, but through tangible transformations in the landscapes they know. These photo pairs make such shifts visceral—showing us exactly what it means when winter temperatures hover just above rather than just below freezing, or when the rain-snow line creeps higher each year. In the absence of long-term snowpack data, these images act as an alternative archive—the kind of evidence that Sheila Jasanoff argues is necessary to fully comprehend environmental change.

Looking out over slopes that once reliably held snow through March, I’m struck by how quickly the familiar has become foreign. The disappearing winters of Mount Lemmon represent more than lost recreation; they signal fundamental shifts in the Southwest’s water systems, ecosystems, and cultural landscapes. Through systematic photo-matching in this overlooked place, we create not just a record of loss but a methodology for expanding our understanding of where and how climate change manifests. These images challenge assumptions about which places deserve careful observation and documentation, urging us to look beyond traditional monitoring networks to the margins, where seemingly small changes foreshadow broader transformations.

Skiing in the Sonoran Desert was always an improbable proposition—a cosmic joke that, for decades, defied expectation. Now, as climate change reshapes our understanding of what’s possible and what’s sustainable, Mount Lemmon’s transformation from a reliable winter retreat to an ephemeral snow zone offers crucial lessons about adaptation, documentation, and the importance of paying attention to change in unexpected places. These photo pairs, capturing dramatic shifts over just two years, remind us that even our most basic assumptions about climate stability may need revision. In this way, Mount Lemmon is both warning and methodology—showing us not just what we are losing, but how we might better document and understand environmental change in all the places we once thought too marginal to matter.

Learning from the Margins: Lessons for Northern Winters

Mount Lemmon’s transformation from an improbable ski destination to a harbinger of climate change offers crucial insights for winter communities far beyond the Sonoran Desert. Climate projections indicate that by mid-century, winter temperatures across North America will rise by an average of 2–4°C, with warming even more pronounced at higher elevations and latitudes. This steady rise pushes the rain-snow threshold—typically around 0°C—higher in elevation, shifting where and how winter can exist. By 2050, studies suggest that many low-elevation ski resorts will face conditions similar to what Mount Lemmon experiences today. With each 1°C increase, the rain-snow line moves roughly 150 meters upward, threatening not just winter recreation, but the entire hydrological systems that communities and ecosystems have depended on for generations.

The struggle unfolding in the Southwest today offers a glimpse of the challenges ahead. Arizona Snowbowl, near Flagstaff—nearly 3,000 feet higher than Mount Lemmon—has turned to artificial snowmaking as a survival strategy. But even this technological fix is proving fragile. The resort’s decision to use reclaimed wastewater for snow production sparked prolonged legal battles with Native American tribes, who consider the San Francisco Peaks sacred. This conflict underscores a broader reality: climate adaptation is rarely just a technical problem—it is entangled with cultural values and water rights. Even with snowmaking capabilities, Snowbowl and other Southwest ski areas face growing constraints. What was once a reliable insurance policy is becoming a precarious gamble. Snowmaking windows—periods when temperature and humidity allow for artificial snow production—have shrunk by up to 30% in some regions over the past three decades, making it harder to sustain operations.

These challenges at the margins of winter reveal something deeper about how we understand environmental change. While scientific data—temperature records, snowpack measurements, climate models—provides essential insights, it also shapes how we perceive both problems and solutions. As Sheila Jasanoff’s work suggests, scientific frameworks and monitoring systems reflect particular ways of seeing the world—often reinforcing assumptions about where climate impacts “matter” while overlooking others. The photo pairs from Mount Lemmon offer a compelling counterpoint: they capture not just physical change, but the transformation of human relationships with landscape, culture, and climate. This merging of scientific and experiential knowledge will only become more critical as winter becomes more precarious across North America.

The changes documented here today—through both quantitative measurements and qualitative observation—may well preview what’s coming to Vermont’s Green Mountains, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, or the lower elevations of Colorado. But more importantly, Mount Lemmon’s story reminds us that addressing climate change requires looking beyond traditional scientific metrics. To fully understand and respond to these shifts, we must ask: How are these changes affecting the communities, cultures, and ways of life built around winter? By learning to document and value multiple forms of knowledge now—especially in places where winter is already marginal—we prepare not just tools, but wisdom, that will prove essential as these transformations spread northward.

Homer’s Odysseus knew that to survive, he had to resist the call of the Sirens—the seductive voices that lured sailors to their doom. Today, the sirens take another form: the comforting idea that winter will always return, that the climate will right itself, and that snow will fall again. But the lesson of Mount Lemmon is clear—the world is changing whether we are ready or not. The question is whether we will steer ourselves toward adaptation or let nostalgia pull us into ruin.

This blog was made possible by POW Brand Alliance partner Keen

Author: Len Necefer and Aaron Mike

Len Necefer, Ph.D., is the CEO & Founder of NativesOutdoors – a native-owned athletic and creative collective. Aaron Mike is a Diné rock climbing athlete at NativeOutdoors, owner/ head guide of Pangaea Mountain Guides, and Native Lands Regional Coordinator at Access Fund.