The History of Climate Science and Politics

Photo by POW Creative Alliance Captain Emily Tidwell

The media often emphasize how much is unknown about climate change, but scientists have understood the basic science behind it for 150 years. Early researchers discovered the greenhouse effect in the mid-1800s, and atmospheric scientists have agreed that the greenhouse effect has been capable of changing Earth’s climate since the 1970s. Nevertheless, many Americans have been taught to doubt the very real threat of human-caused climate change.

The evidence supporting this science is written in the Earth itself. Layers of ancient ice in Greenland and Antarctica preserve a record of past atmospheric conditions. The longest ice cores, reaching depths of 3 km, reveal that CO₂ levels began rising sharply with industrialization, far beyond natural fluctuations over the past 800,000 years. These frozen records provide a clear, undeniable picture that human activity has pushed the climate into uncharted territory.

Long before ice cores confirmed it, scientists were already uncovering the role of greenhouse gases. In 1856, Eunice Foote became the first person to demonstrate that carbon dioxide absorbs and radiates heat. She was not alone. Following World War II, atmospheric scientists confirmed and built on these early researchers’ conclusions.

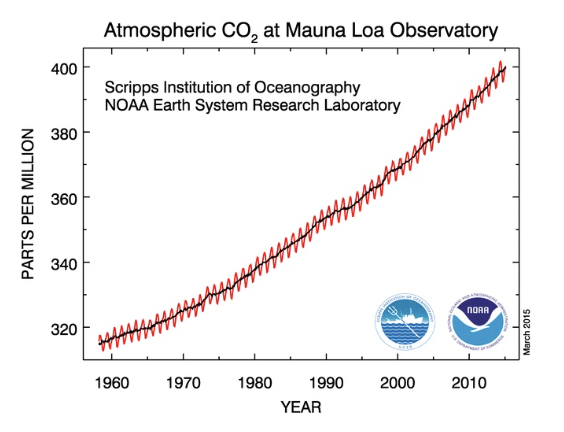

Starting in the late 1950s, a man named Charles Keeling developed the first computer model of human-caused global warming, known as the Keeling Curve. Over two years, he collected data on carbon levels in the atmosphere and compared them to global mean temperatures. He found a direct relationship between carbon emissions and global temperature. Future research confirmed his findings.

Building on this work, in the 1970s, NASA scientist James Hansen developed a general circulation model that distinguished long-term climate shifts from independent weather variations. The new model dramatically improved scientists’ ability to predict the impact of carbon dioxide on the climate.

How the Fossil Fuel Industry and Government Challenged Climate Science

At the time, the fossil fuel industry took global warming seriously. In the 1970s, the American Petroleum Institute developed a committee called the “CO2 and Climate Task Force” to monitor the latest developments in climate science. In 1980, they were warned by John Laurmann, a scientist at Stanford University, that global warming would have “globally catastrophic effects” by 2060. The American Petroleum Institute proceeded to push for further coal production globally, insisting that it would have no negative consequences.

Hansen published his findings in Science in 1981. He explained that rising sea levels would likely flood almost all major port cities.

Scientists like Hansen had long believed that good science would drive politicians to act for the greater good. In retrospect, the belief was naïve at best. The Reagan administration immediately pulled funding from Hansen, hoping to cripple his research.

This was also one of the first instances of systematic efforts to cast doubt on climate science. In 1983, the Reagan administration released a joint report by atmospheric scientists and economists. The physical scientists demonstrated that rising carbon dioxide levels were a serious problem. The economists made a different argument. They contended that it was impossible to know how the economy would function in fifty or one hundred years. Thus, economic action was irresponsible based on what the economists, not the scientists, presented as weak science. Although there was a dramatic disagreement, the report summary (which is all that most politicians read) presented the economists’ conclusion, not the scientists.

Despite the administration’s best efforts, atmospheric scientists continued to press forward. In 1988, Hansen explained three things at a Senate hearing. First, global warming was already occurring. Second, atmospheric scientists agreed that global warming was real. Third, there was a clear link between fossil fuels and carbon dioxide.

The testimony made waves. Publications from The New York Times to largely apolitical magazines like Ski published stories on global warming. With global warming filling the newspaper pages, George H. W. Bush added global warming to his 1988 presidential platform, arguing that the problem could only be solved through decisive government action.

That same year, the United Nations formed the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In response, the energy industry, which had the most to lose, organized in an attempt to spread doubt about the legitimacy of climate science.

The Struggle for Public Awareness

By the early 1990s, the fossil fuel industry had been aware of global warming for over thirty years. Historians trace the first mention of the greenhouse effect to an energy conference in 1959, when Edward Teller, who helped invent the hydrogen bomb, warned oil executives that continued fossil fuel use could submerge all coastal cities.

Exxon, Shell, and Total had long studied the issue. Perhaps most famously, in 1982, Exxon developed a 40-page report that accurately predicted many of the consequences of global warming we see today. Shell followed with a similar report in 1986, and Total had been producing studies since the 1970s. Despite the overwhelming evidence, the general public remained largely unaware of these findings until the past decade, when journalists and historians pored over thousands of pages of internal documents.

In 1989, Exxon and other energy corporations formed the Global Climate Coalition (GCC). The coalition operated on two fronts: countering government and independent climate studies with reports from a small group of scientists who spread false or misleading information about global warming. These scientists were rarely climate experts, yet the media presented their findings as equally credible to studies conducted by actual atmospheric scientists. Historian Naomi Oreskes later dubbed these actors the “merchants of doubt.”

Initially, these efforts had only partial success. During the 1990s, Americans’ concern about climate change grew, but it dropped sharply in the early 2000s. In 2000, 71% of Americans said they were worried about global warming; by 2004, that number fell to 51%. By 2011, nearly half of Americans—48%—believed the threat was exaggerated, up from 31% in 1997.

This declining concern stood in stark contrast to the rising prominence of climate change in pop culture. Fictional films like The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and documentaries such as former Vice President Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth became box-office hits, with Gore’s film grossing over fifty million dollars globally. While the energy industry gradually stopped outright denying global warming, they continued to downplay its severity, contradicting their own research.

In response to growing awareness, a new generation of climate activists emerged. In 2014, 350.org organized the People’s Climate March, drawing an estimated 300,000 Americans and thousands more globally. Three years later, the Sunrise Movement mobilized to elect politicians dedicated to climate action.

Yet these efforts have had limited impact. While the number of Americans who believe temperatures are rising has remained relatively stable—rising from 74% to 76% between 1997 and 2020—the oil industry has largely succeeded in keeping climate change out of the nation’s top political priorities, despite knowing the stakes since the 1970s. As James Black, Exxon’s Scientific Advisor, warned in a 1977 report to management:

“In the first place, there is general scientific agreement that the most likely manner in which mankind is influencing the global climate is through carbon dioxide release from the burning of fossil fuels. Present thinking holds that man has a time window of five to 10 years before the need for hard decisions regarding changes in energy strategies might become critical.”

This lack of consistent political support has hampered efforts by the Obama and Biden administrations to enact meaningful climate reforms. Republican-controlled Congresses and the Trump administration consistently rolled back climate policies. Effective climate action requires continuity and commitment, something that has been repeatedly undermined over the past several decades.

The speckled history of global warming offers insights moving forward. First, scientific facts are not enough to inspire a majority of voters or politicians to take climate action. Scientists need to embrace politics, actively lobby for political action, and educate the public. Second, over the past thirty-seven years, Americans have managed to mobilize through politics and pop culture. There is potential for climate action, provided voters can keep their focus and accept that benefits will be slow in coming. Finally, the energy industry cannot be trusted. It is essential to diminish the influence of energy companies over federal energy and climate policy if we are going to stand a chance at slowing global warming.

Author: Jesse Ritner

Jesse Ritner is an Assistant Professor of History at Georgia College & State University. He specializes in twentieth-century United States history, environmental history, and environmental justice. More specifically, his research investigates the intersections of climate adaptation, technology, capitalism, race, and culture. Outside of work, Jesse is an avid skier and backpacker, as well as a […]