Beyond the Ice: Understanding the Far-Reaching Impacts of Glacier Loss

Defined by their immense size and slow, steady flow, glaciers hold stories of Earth’s past—and warnings for its future.

2025 is the United Nations International Year of Glacier Preservation, a global call to understand and address the rapid loss of glaciers and its wide-reaching effects on people and ecosystems. To dive deeper into these impacts, we teamed up with POW Science Alliance member and glaciologist Dr. Mauri Pelto to uncover what’s at stake on a global scale.

The urgency couldn’t be clearer. Glacier loss has accelerated at an alarming rate, raising serious concerns among scientists. Data from the World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS), which tracks roughly 60 reference glaciers, paints a stark picture. In 2023, for the first time, all 59 reporting glaciers showed a negative mass balance, meaning they all lost ice. Alarmingly, this trend continued in 2024, affecting glaciers across the Arctic, high-altitude mountains, and mid-latitude regions. The rapid disappearance of glaciers has led to the creation of a new data layer within the Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) inventory, specifically for extinct glaciers. This has also led to the development of the Global Glacier Casualty List.

This increased ice loss signals that glaciers are now out of equilibrium with current climatic conditions. The implications are severe, as glaciers provide crucial water resources for aquatic life, hydroelectric power, irrigation, and drinking water. We examined four regions where glacial loss is already impacting local communities.

Let’s take a look.

Pacific Northwest, USA:

Glaciers are the lifeblood of rivers like the Fraser and Nooksack, sustaining salmon populations essential to ecosystems, Indigenous traditions, and outdoor economies. The Fraser River, fed by 2,600 glaciers, has seen drastic declines in salmon numbers. Over the last five years, Chum salmon populations have dropped to 625,000 from a long-term average of 1.5 million, Sockeye have declined from 4.7 million to 1.8 million, and Chinook are at historic lows (Pacific Salmon Foundation).

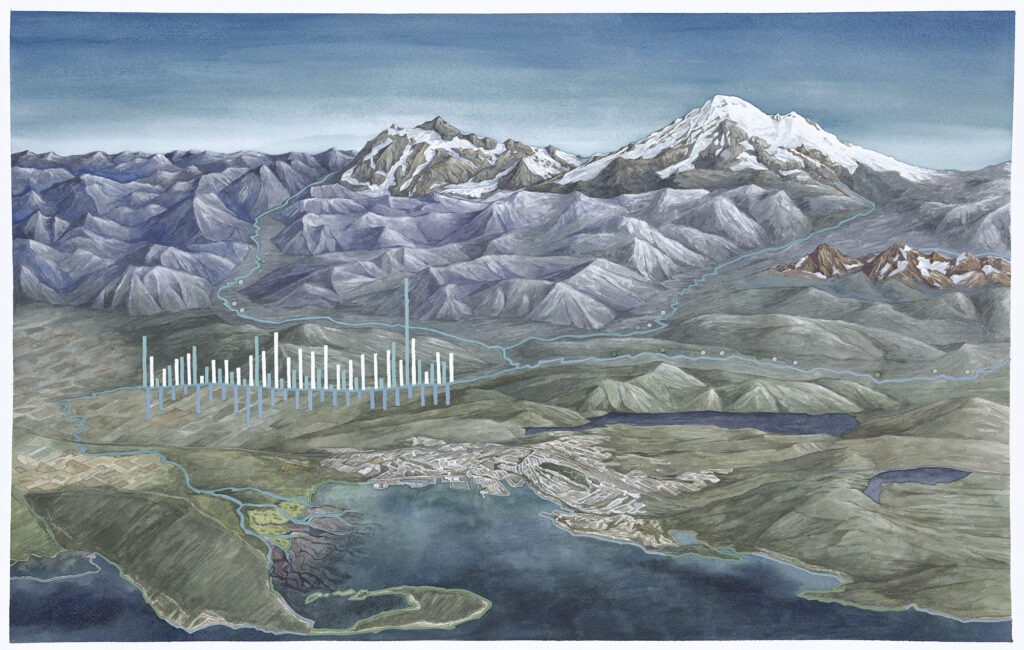

A similar story is happening in Washington’s Nooksack River, where glaciers act as a cooling system, keeping streamflow steady and temperatures in check, which is critical for salmon survival during summer heatwaves. Our research from 2010 to 2021 found that glaciated sections of the river experienced a 24% increase in summer water flow during extreme heat, which helped salmon survive. In glacier-free sections, however, streamflow dropped by 20%, and water temperatures rose over 2°C, beyond what many salmon can tolerate.

The graphs tell a powerful story about glaciers’ role in the Nooksack River watershed. During heat waves, the glaciated North Fork sees a 23% increase in river flow, thanks to glacial melt, while the unglaciated South Fork drops by 20%. This striking contrast shows just how essential glaciers are for sustaining water flow—and life—in Whatcom County.

When glaciers shrink and salmon disappear, the ripple effects are enormous: wildlife that rely on salmon for food, like bears and eagles, are left struggling to find food. Indigenous communities lose a critical cultural and nutritional resource. Recreational fishing and tourism take a hit, threatening local businesses and outdoor economies that rely on healthy rivers. Protecting these frozen reservoirs isn’t just about climate, it’s about keeping the places we love and the industries they support thriving.

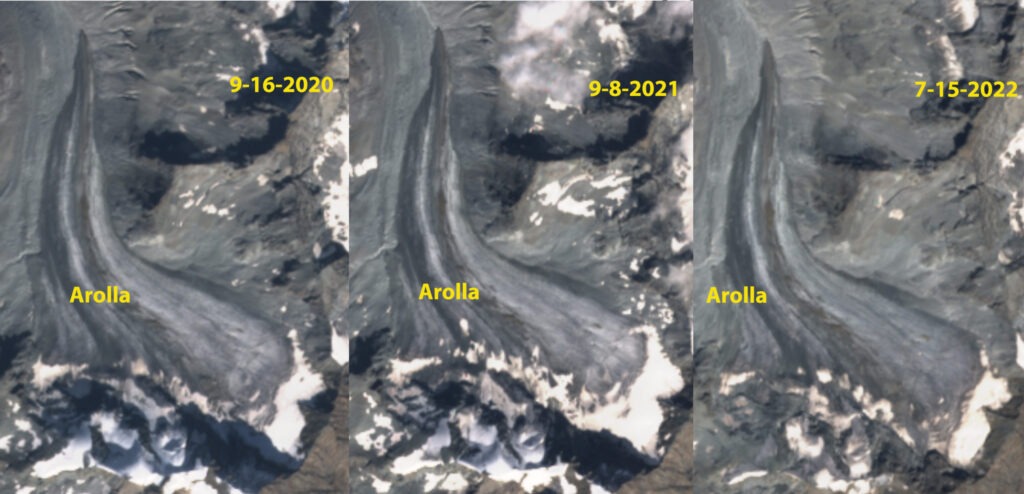

European Alps:

Across Europe, melting glaciers currently sustain major hydropower systems that provide electricity to millions. But as glaciers continue to retreat, this vital source of energy is at risk of diminishing.

Switzerland’s Grand Dixence Dam, the world’s largest gravity dam, relies on meltwater from 35 glaciers to fill its reservoir by late September. Austria, where 70% of electricity comes from hydropower, depends on glacier-fed projects like Kaprun, which generates 700 MW—60% of its water comes from the fast-retreating Pasterze Glacier, which is now shrinking by 175 meters per year.

France’s Rhone River, home to 19 hydropower plants supplying 25% of the country’s hydropower, starts at the Rhone Glacier. The river is also fed by the Gross Aletsch, the Alps’ largest glacier—another ice reserve that’s disappearing fast.

Why does this matter? Millions of people rely on glacier-fed hydropower for clean, reliable energy. As glaciers shrink, energy production becomes less predictable, impacting electricity costs, grid stability, and communities that depend on these resources.

Asia:

Asia’s high mountain glaciers are crucial for downstream communities, particularly during the pre-monsoon period. In the Indus basin, up to 60% of irrigation water comes from glacier melt, supporting 11% of total crop production. This translates to 129 million farmers relying on this meltwater to feed 38 million people. However, earlier glacier melt is creating a mismatch—more water is available early in the season, but less when crops need it most in July and August, leading to increased groundwater depletion.

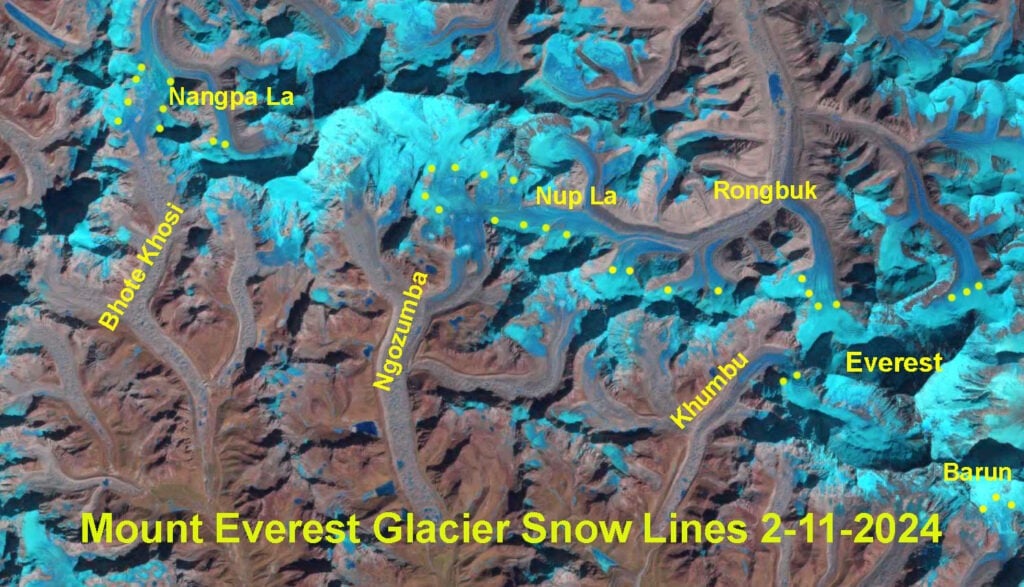

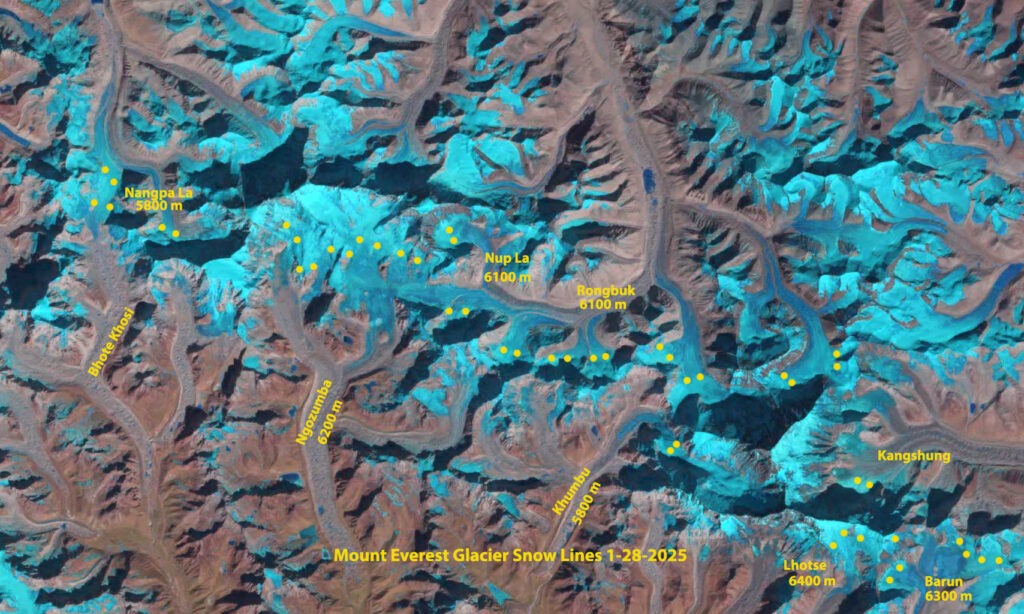

The Koshi River Basin in Nepal tells a similar story. It had 2,061 glaciers covering 3,225 km² in 2009, but lost 19±5.6% of its glacier area between 1976 and 2009. This loss directly impacts the Sunsari Morang irrigation scheme, which waters 68,000 hectares. During the dry season (November to May), when vital crops like wheat, pulses, and vegetables are grown, river levels drop, which limits irrigation and threatens food security. In the last two winters, we have observed that the glacier snowline on Mount Everest has risen and then remained at approximately 6000 m, illustrating the lack of winter snowfall to provide winter and spring runoff.

Melting glaciers are disrupting water availability, impacting millions of farmers and threatening food production in these regions. The changing timing and volume of meltwater pose a critical challenge for communities that rely on consistent irrigation. This means potential food shortages, economic hardship, and increased pressure on already-strained water resources.

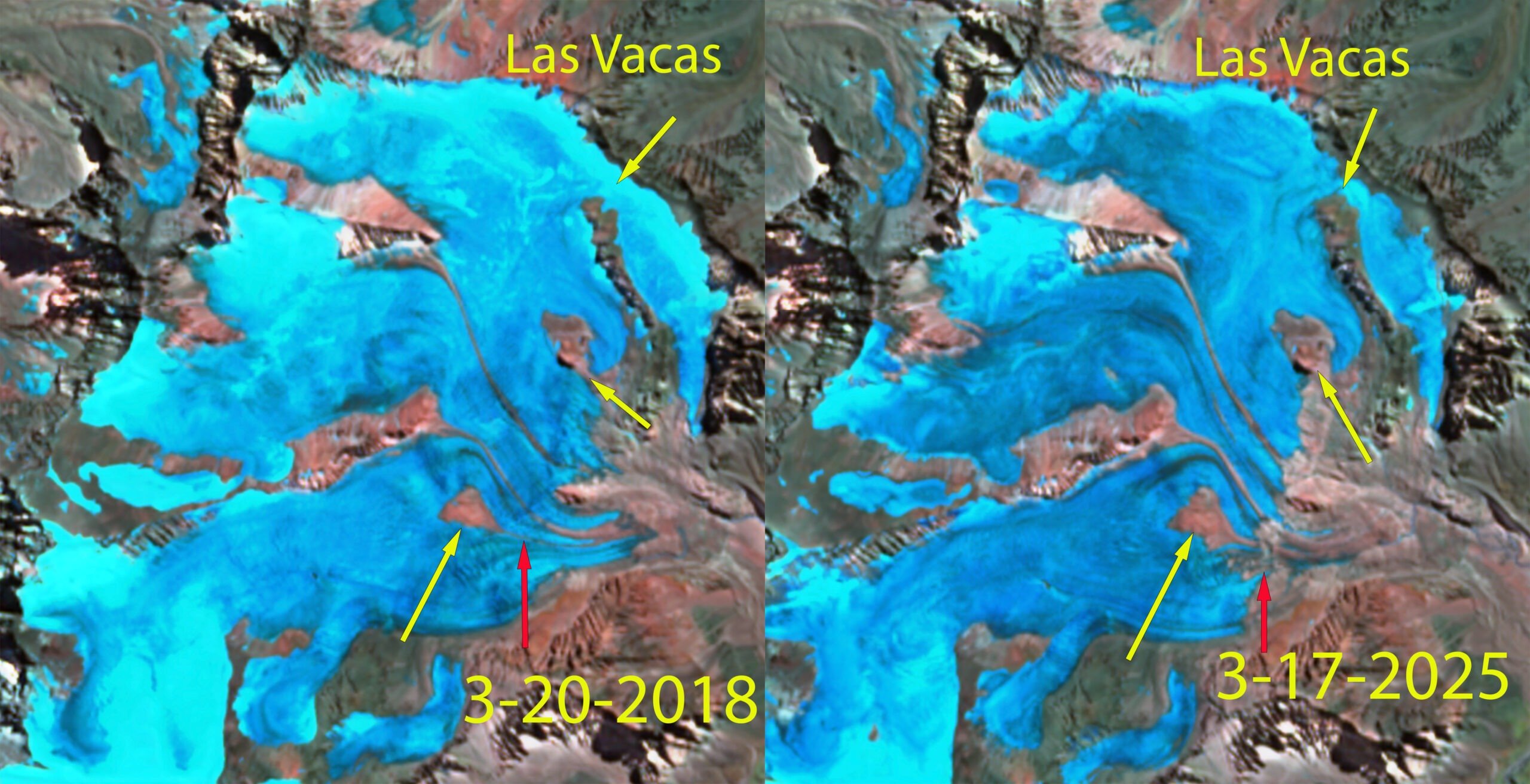

South America’s Andes:

In Chile and Bolivia, glaciers are critical lifelines for water security. In Chile’s Santiago Metropolitan area—home to 8 million people—the Maipo River, fed by glaciers, provides 70% of drinking water and 90% of irrigation. During a recent drought (2010-2018), the contribution of glacier runoff to the river increased to 16% ± 6% (from 11% ± 5%), primarily due to a significant decrease in discharge from the basin. This highlights the glaciers’ importance when other water sources dwindle. In summer, glaciers contribute 34% of the river’s flow.

Similarly, La Paz, Bolivia, relies on 70 glaciers for 15% of its annual water, a crucial 27% during the dry season (1997-2006). More recently (2000-2019), glacier contribution has increased to 22% of total runoff, not due to increased melt, but due to reduced overall river flow.

This means that as glaciers shrink, these communities face a double threat: less water overall and a reduced buffer against drought. The increasing reliance on glacier melt highlights the vulnerability of these regions, and the projected decline in glacier runoff will exacerbate water scarcity, impacting drinking water, agriculture, and the overall well-being of millions.

The Path Forward:

These case studies highlight the essential role glaciers play in sustaining communities, ecosystems, and economies. Their loss disrupts food security, water availability, energy production, and livelihoods around the world. While some glaciers are vanishing too quickly to save, many can still be preserved, but only if we act now.

That means pushing for bold climate policy, transitioning to clean energy, and cutting emissions at every level—from local advocacy to federal legislation. Individual choices matter, but collective action is how we move the needle. By protecting these frozen reservoirs, we protect the rivers we paddle, the slopes we ride, and the communities that rely on them.

Author: Dr. Mauri Pelto

Dr. Mauri Pelto has been a Associate Provost at Nichols College and Professor of Environmental Science at Nichols College in Massachusetts since 1989. Additionally, Pelto is a Glaciologist and has been the Science Director of the North Cascade Glacier Climate Project since 1984. This project monitors the mass balance and behavior of more glaciers than […]